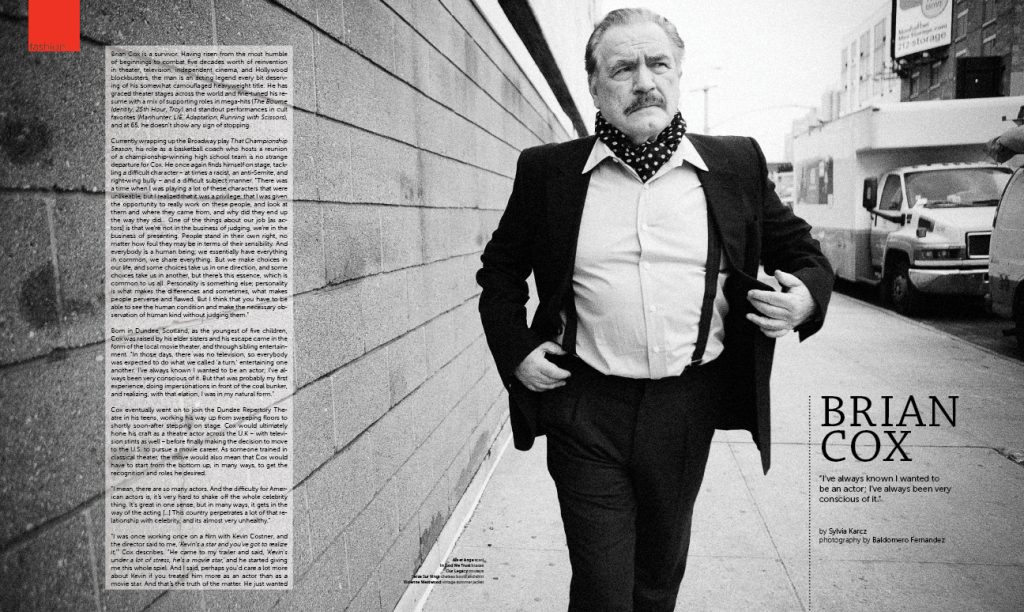

By Sylvia Karcz

Photography by Baldomero Fernandez

“I’ve always known I wanted to be an actor; I’ve always been very conscious of it.”

Brian Cox is a survivor. Having risen from the most humble of beginnings to combat five decades worth of reinvention in theater, television, independent cinema, and Hollywood blockbusters, the man is an acting legend every bit deserving of his somewhat camouflaged heavyweight title. He has graced theater stages across the world and fine-tuned his resume with a mix of supporting roles in mega-hits (The Bourne Identity, 25th Hour, Troy) and standout performances in cult favorites (Manhunter, LIE, Adaptation, Running with Scissors), and at 65, he doesn’t show any sign of stopping.

Currently wrapping up the Broadway play That Championship Season, his role as a basketball coach who hosts a reunion of a championship-winning high school team is no strange departure for Cox. He once again finds himself on stage, tackling a difficult character – at times a racist, an anti-Semite, and right-wing bully – and a difficult subject manner. “There was a time when I was playing a lot of these characters that were unlikeable, but I realized that it was a privilege; that I was given the opportunity to really work on these people, and look at them and where they came from, and why did they end up the way they did… One of the things about our job [as actors] is that we’re not in the business of judging, we’re in the business of presenting. People stand in their own right, no matter how foul they may be in terms of their sensibility. And everybody is a human being; we essentially have everything in common, we share everything. But we make choices in our life, and some choices take us in one direction, and some choices take us in another, but there’s this essence, which is common to us all. Personality is something else; personality is what makes the differences and sometimes, what makes people perverse and flawed. But I think that you have to be able to see the human condition and make the necessary observation of human kind without judging them.”

Born in Dundee, Scotland, as the youngest of five children, Cox was raised by his elder sisters and his escape came in the form of the local movie theater, and through sibling entertainment. “In those days, there was no television, so everybody was expected to do what we called ‘a turn,’ entertaining one another. I’ve always known I wanted to be an actor; I’ve always been very conscious of it. But that was probably my first experience, doing impersonations in front of the coal bunker, and realizing, with that elation, I was in my natural form.”

Cox eventually went on to join the Dundee Repertory Theatre in his teens, working his way up from sweeping floors to shortly soon-after stepping on stage. Cox would ultimately hone his craft as a theatre actor across the U.K – with television stints as well – before finally making the decision to move to the U.S. to pursue a movie career. As someone trained in classical theater, the move would also mean that Cox would have to start from the bottom up, in many ways, to get the recognition and roles he desired.

“I mean, there are so many actors. And the difficulty for American actors is, it’s very hard to shake off the whole celebrity thing. It’s great in one sense, but in many ways, it gets in the way of the acting […] This country perpetrates a lot of that relationship with celebrity, and its almost very unhealthy.”

“I was once working once on a film with Kevin Costner, and the director said to me, ‘Kevin’s a star and you’ve got to realize it,’” Cox describes. “He came to my trailer and said, ‘Kevin’s under a lot of stress, he’s a movie star,’ and he started giving me this whole spiel. And I said, perhaps you’d care a lot more about Kevin if you treated him more as an actor than as a movie star. And that’s the truth of the matter. He just wanted to act. The other stuff is the baggage that you acquire along the way. Fundamentally, all you want to do is the job.”

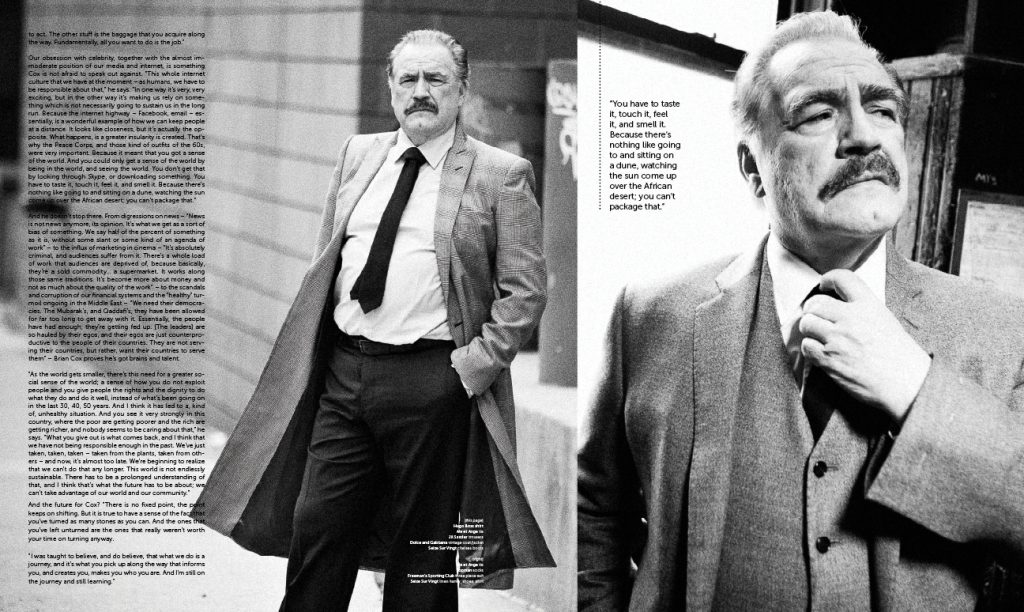

Our obsession with celebrity, together with the almost immoderate position of our media and internet, is something Cox is not afraid to speak out against. “This whole internet culture that we have at the moment – as humans, we have to be responsible about that,” he says. “In one way it’s very, very exciting, but in the other way it’s making us rely on something which is not necessarily going to sustain us in the long run. Because the internet highway – Facebook, email – essentially, is a wonderful example of how we can keep people at a distance. It looks like closeness, but it’s actually the opposite. What happens, is a greater insularity is created. That’s why the Peace Corps, and those kind of outfits of the 60s, were very important. Because it meant that you got a sense of the world. And you could only get a sense of the world by being in the world, and seeing the world. You don’t get that by looking through Skype, or downloading something. You have to taste it, touch it, feel it, and smell it. Because there’s nothing like going to and sitting on a dune, watching the sun come up over the African desert; you can’t package that.”

And he doesn’t stop there. From digressions on news – “News is not news anymore, its opinion. It’s what we get as a sort of bias of something. We say half of the percent of something as it is, without some slant or some kind of an agenda of work” – to the influx of marketing in cinema – “It’s absolutely criminal, and audiences suffer from it. There’s a whole load of work that audiences are deprived of, because basically, they’re a sold commodity… a supermarket. It works along those same traditions. It’s become more about money and not as much about the quality of the work” – to the scandals and corruption of our financial systems and the “healthy” turmoil ongoing in the Middle East – “We need their democracies. The Mubarak’s, and Qaddafi’s, they have been allowed for far too long to get away with it. Essentially, the people have had enough; they’re getting fed up. [The leaders] are so hauled by their egos, and their egos are just counterproductive to the people of their countries. They are not serving their countries, but rather, want their countries to serve them” – Brian Cox proves he’s got brains and talent.

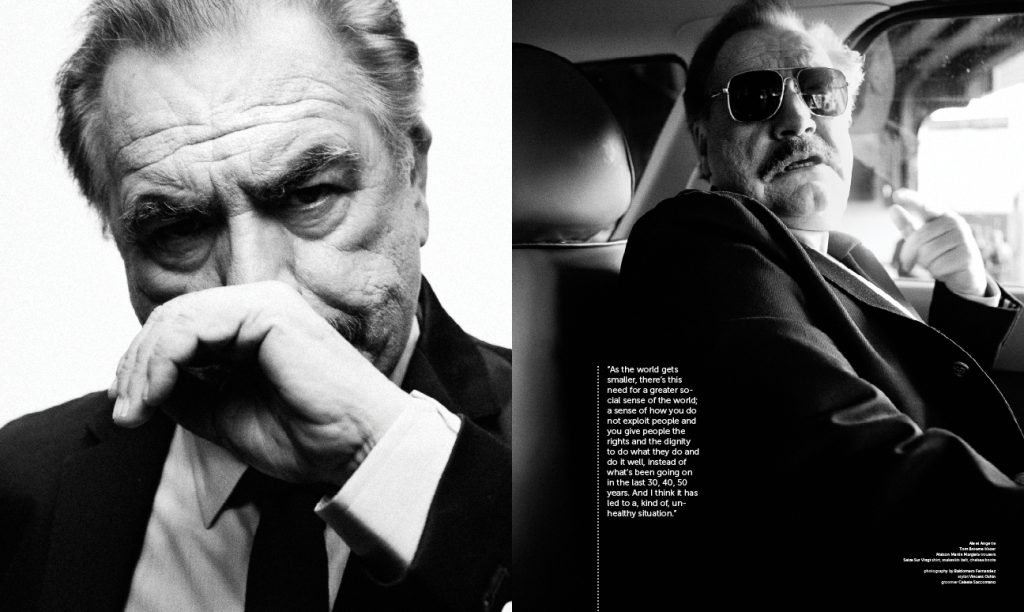

“As the world gets smaller, there’s this need for a greater social sense of the world; a sense of how you do not exploit people and you give people the rights and the dignity to do what they do and do it well, instead of what’s been going on in the last 30, 40, 50 years. And I think it has led to a, kind of, unhealthy situation. And you see it very strongly in this country, where the poor are getting poorer and the rich are getting richer, and nobody seems to be caring about that,” he says. “What you give out is what comes back, and I think that we have not being responsible enough in the past. We’ve just taken, taken, taken – taken from the plants, taken from others – and now, it’s almost too late. We’re beginning to realize that we can’t do that any longer. This world is not endlessly sustainable. There has to be a prolonged understanding of that, and I think that’s what the future has to be about; we can’t take advantage of our world and our community.”

And the future for Cox? “There is no fixed point, the point keeps on shifting. But it is true to have a sense of the fact that you’ve turned as many stones as you can. And the ones that you’ve left unturned are the ones that really weren’t worth your time on turning anyway.

“I was taught to believe, and do believe, that what we do is a journey, and it’s what you pick up along the way that informs you, and creates you, makes you who you are. And I’m still on the journey and still learning. You have to taste it, touch it, feel it, and smell it. Because there’s nothing like going to and sitting on a dune, watching the sun come up over the African desert; you can’t package that… As the world gets smaller, there’s this need for a greater social sense of the world; a sense of how you do not exploit people and you give people the rights and the dignity to do what they do and do it well, instead of what’s been going on in the last 30, 40, 50 years. And I think it has led to a, kind of, unhealthy situation.”