Interview: Moonah Ellison

Story: Chesley Turner

Photography: Dennys iLic

Très élégant, super sophistiqué,

charmante, et tellement gentil.

Can we also mention she is

the smartest person in the room.

Errr… Any Room ! !

Huma Abedin is a woman who handles pressure while maintaining grace and staying grounded. For her, perhaps this shouldn’t be a surprise. It’s about roots.

“My dad would say, you know, a person is like a plant; and a plant is only as good as its roots.” For Huma, those roots were formed not by any single town or place, or even moment, but rather by parents who had a sense of self and ancestry. They also had a global curiosity and confidence. It was all inherited by their daughter.

“My parents immigrated to America. They were Fulbright Scholars. But when I was two, my dad was essentially diagnosed with a terminal illness. He was told he had five to ten years.” Facing a choice, he could either get his affairs in order and settle in for the long decline or, “go out and live the most extraordinary life he could live while he had time on this earth.” Sayed Zainul Abedin chose the latter.

Two months later, the Abedin family moved from Kalamazoo, MI to Saudi Arabia. “We were raised with this real sense of knowing where we came from, understanding who we were.” That self-identity was complex. Huma’s parents had immigrated to America – her father from India and her mother from Pakistan, two countries at war and had established a very Midwestern life. Now, the family settled into life in Jeddah, a city on the western edge of the country, on the coast of the Red Sea, finding a new way of life.

But before you can be found, you must first experience being lost. One of Huma’s earliest such memories is seared into her memory. She tells the story viscerally:“We went to the souk to shop. This was before the days of cellphones, and many people didn’t speak English. My parents didn’t speak Arabic yet. Here I am, this little American child overwhelmed by all the senses and smells of the shawarma, you know, the incense, and seeing all the dates. And all the women had to be covered back then; all the women were dressed in these black abayas. I grabbed onto somebody else’s abaya thinking it was my mom and walked along with her. It was only when I looked up, I realized it wasn’t my mother.”

Huma’s mother, Saleha, has said this was one of the worst experiences of her life. Huma doesn’t focus on her own fear in that moment, but she does remember her mother’s. “It was the first time I had ever seen my mother cry.” Despite growing up in Saudi Arabia with an Indian father and Pakistani mother, the family identified as American. “My parents had lived the American Dream. It was this notion of choice and freedom, and self determination, and core to what it is to be an American living in a democracy. So, we were raised as American and as Muslims.”

Still, Abedin says, “I was curious about other people and other cultures.” Both Sayed and Saleha worked in academia, so the family had time to travel the world during the summers. At seven teen, Abedin moved back to the United States to attend George Washington University.

“I think people should communicate. I mean, you know, women particularly. Women – we do have our own sort of oral history.

Her father, anticipating the impending drastic change in her environment, sent her forth with words of wisdom. “He said,‘You will have total freedom. You can make whatever choice that you want, but I just want to remind you of one thing: that no freedom in this world is absolute. Every choice you make in your life is going to have consequences.’”

Those words, Huma says, are what grounded her, rooted her, and gave her the confidence to venture into the world’s challenges. “This deep faith and love,like—yes—love of my faith. Knowing where I came from and who I was and being able to walk into the White House at age twenty-one, kind of excited about how different I was and proud of what I knew that was different from a lot of the people around me; curious about the world.”

Abedin is adamant that representation matters. It is imperative for young girls and women to see themselves in the world be-fore they themselves seek to make a place in it, to know it is possible to attain roles of significance and leadership and impact.In her own life, the visible role model was Christiane Amanpour on CNN International during the Persian Gulf War. “Seeing this woman appear on my screen, she looked like she came from my part of the world.If she was blonde, blue-eyed, named Mary Smith, I’m not sure I would have had the same reaction. But to me, she seemed like this extraordinary truth-teller, and just so brave, and strong, and smart. So, I went to university to become Christiane Amanpour.”

While at GW, Abedin first studied journalism and then focused on politics and international relations. A friend told her, “If you want to be Christiane Amanpour, go intern for Mike McCurry,” the White House Press Secretary for Bill Clinton. But after being accepted into the White House internship program, she wasn’t put anywhere in the press office. She was sent to First Lady Hillary Clinton.

“They picked me. I was put in the First Lady’s office given my background, and my mother was a big activist and advocate for women and given Hillary’s experience in Beijing…. They saw something, and they picked me.”

However, despite this vote of confidence,Huma was still recovering from the very real impact of losing her father. He had passed away right before she had left home for university. “I was so in shock. We children didn’t know how ill he was, and to me he was a superhero even though he weighed ninety pounds in the months before he passed away. And I wasn’t able,for years, to tell anybody that he was gone,that it was difficult for me to lose him.” That trauma of loss made Huma close herself off a bit, and often seek to be behind the scenes rather than in the spotlight. “I was always prepared to work hard and do the best I could at my job, [but] I never wanted to be the center of attention. That is a direct result of having lost my dad.”

Many people know the deep and enduring relationship – a mentorship and a friend-ship – that grew between Huma Abedin and Hillary Clinton. Huma was at Hillary’s side as they weathered all sorts of triumphs, empowered moments, but also defeats. Remembering the preamble to the 2016 campaign,Huma says, “She served four years, success-fully, as Barack Obama’s Secretary of State,and, you know, it’s history now but back then it really felt as though [running for President]was the necessary thing to do. She was the most qualified candidate.”

Despite the eminent qualifications, and despite all they had learned from the defeat to President Obama in 2008, the field was not welcoming. “The journey of a woman politician campaigning, and all the misogyny and sexism, the double-standards… that had reached sort of an epic level. Still, Hillary wanted to do it the old-fashioned way.”

During her run for Senate from New York in1999, Clinton had embarked on a listening tour, meeting people in their homes and at diners, asking what they were thinking,what they were worried about, so that she could be an effective legislator and policymaker. She had the same strategy in mind for the 2016 presidential campaign. But American presidential races are their own kind of crazy.

“See, the way our elections are run are very different from other parts of the world, you know, in UK or New Zealand, where you’re essentially voting for a party. Here, you really are voting for the personality. You have to compete for that space.” And people in this country, the research shows, don’t tend to think women belong in executive leadership positions. It’s one of the reasons representation is so important. We don’t see women in these roles. “It’s much easier for a woman to run for Congress or run for Senate, because to be in a body of collaborative work, that you can see. But to be Commander in Chief? A leader? An Executive? A CEO? We just couldn’t do that.”

After Clinton’s 2016 loss, several female candidates ran in 2020, but the preconceived assumptions of the Presidential race are to change. Abedin keeps this front-of-mind in her work and advocacy. “I spend a lot of my public life calling that out, because that’s the only way we’ll find real solutions. In many ways, we’re actually going backward. The UN Secretary General put out a report saying it’s going to take 300 years for there to be gender equity.”

Women in power, women in visible leadership, and women making decisions for themselves is imperative to create and maintain change. These are all things she saw modeled in Clinton’s office as First Lady.“Hillary did not tolerate women not supporting other women. It was a very collaborative office.There was always room at the table for a young voice or someone less experienced. And, you know, she was always a collector of ideas from arrange of people: older people, her peers, young people. I think that she just felt like you make better, more informed decisions when you have more ideas and perspectives at the table. That’s how I was raised, professionally.”

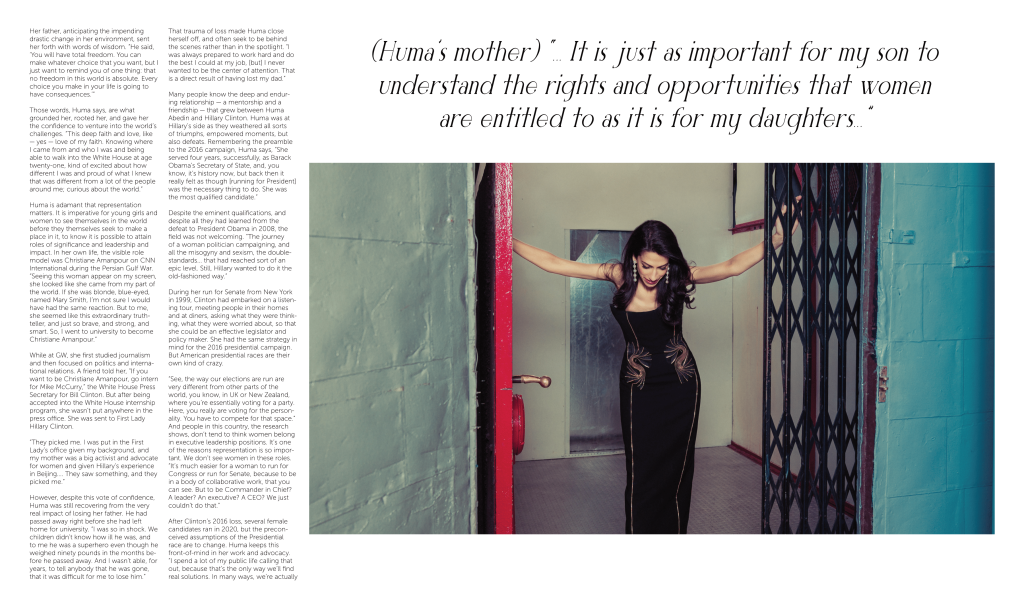

(Huma’s mother) “… It is just as important for my son to

understand the rights and opportunities that women

are entitled to as it is for my daughters…”

Inclusion, representation, validation, and voice were important parts of Huma’s experience. As one of only two Muslims that she knew of in the White House at the time, and as a woman of col-or working with mostly Caucasian colleagues,she re-calls feeling lucky that her differences were embraced .“Frankly,even amongst us women of color, I remember a time where it was like,‘ W e l l ,there’s not enough space for each of us to have leadership.’ And I think what you learn as you get older is that there’s plenty of space.”

There is plenty of space for more than the token representation and hearing from multiple, diverse voices matters. Experience and advocacy extend beyond precise sociological categories. “Psychologically and culturally, we just need to change the system. And it’s not just women who need to change. The whole dynamics of how our society was once structured has changed.”

And this is difficult. That fact seems to endure.It’s hard to have a job and maintain a house-hold. The concept and aspiration for women to “have it all,” may be possible because of the work of Gloria Steinem and our mothers’ generation, but it’s a struggle every day to balance everything and to overcome the cultural stasis that seems so engrained. Huma reiterates that women need to change, but so do men. For her, personally and practically, that means starting with how she raises her own son.

“My intention is to raise him not just to respect women, but also not to fear their power.”Once again recalling the example of her mother, Huma relates the family story when Saleha took her older brother to a women’s conference. At one point, a woman pointed angrily at him and said, “What are you doing here?This conference is for us.” Huma’s mother stepped between them and said, “It is just as important for my son to understand the right sand opportunities that women are entitled to as it is for my daughters.” Of her mother, Huma says, “I think she’s the one who really in stilled in me this notion that we aren’t going to make progress without men at the table.”

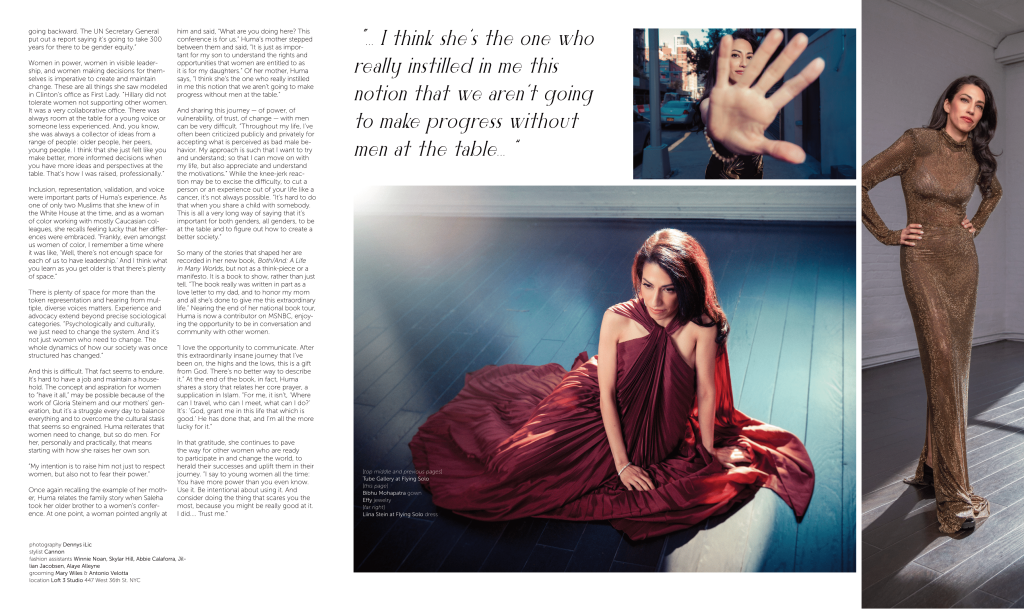

“... I think she’s the one who

really instilled in me this

notion that we aren’t going

to make progress without

men at the table… ”

And sharing this journey—of power, of vulnerability, of trust, of change—with men can be very difficult. “Throughout my life, I’ve often been criticized publicly and privately for accepting what is perceived as bad male behavior. My approach is such that I want to try and understand; so that I can move on with my life, but also appreciate and understand the motivations.” While the knee-jerk reaction maybe to excise the difficulty, to cut a person or an experience out of your life like a cancer, it’s not always possible.“It’s hard to do that when you share a child with somebody.This is all a very long way of saying that it’s important for both genders,all genders, to be at the table and to figure out how to create a better society.”

So many of the stories that shaped her are recorded in her new book, Both/And: A Life in Many Worlds, but not as a think-piece or a manifesto. It is a book to show, rather than just tell. “The book really was written in part as a love letter to my dad, and to honor my mom and all she’s done to give me this extraordinary life.” Nearing the end of her national book tour, Huma is now a contributor on MSNBC,enjoying the opportunity to be in conversation and community with other women.

“I love the opportunity to communicate. After this extraordinarily insane journey that I’ve been on, the highs and the lows, this is a gift from God. There’s no better way to describe it.” At the end of the book, in fact, Huma shares a story that relates her core prayer, a supplication in Islam. “For me, it isn’t, ‘Where can I travel, who can I meet, what can I do?’It’s: ‘God, grant me in this life that which is good.’ He has done that, and I’m all the more lucky for it.”In that gratitude, she continues to pave the way for other women who are ready to participate in and change the world, to herald their successes and uplift them in their journey. “I say to young women all the time:You have more power than you even know.Use it. Be intentional about using it. And consider doing the thing that scares you the most, because you might be really good at it.I did…. Trust me.”