If you want to be educated and understand where you are you have to understand where you've come from and look at what's happening now...

By Pete Barratt

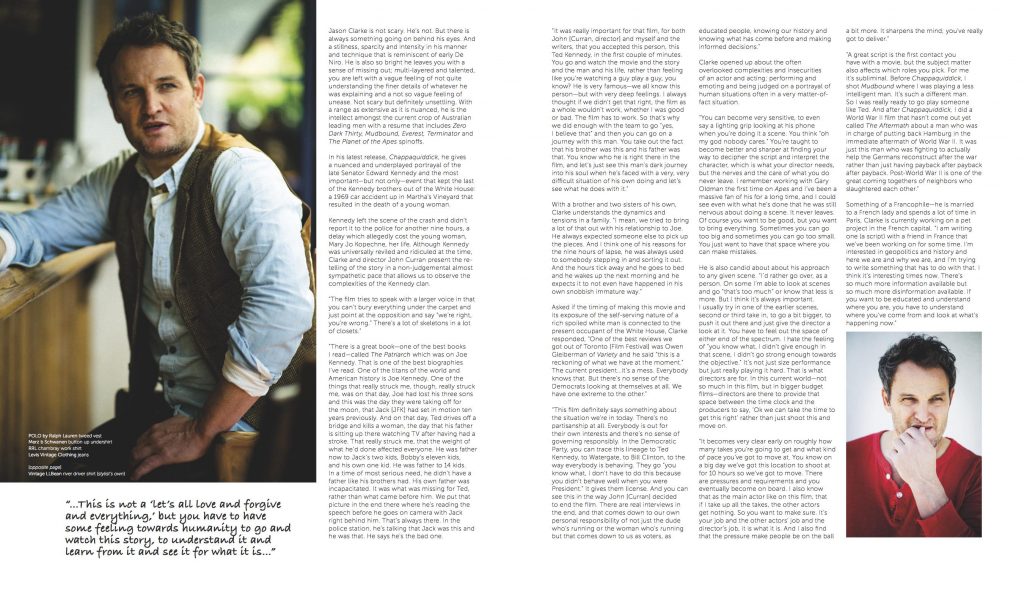

Photography by Michael Muller

Jason Clarke is not scary. He’s not. But there is always something going on behind his eyes. And a stillness, scarcity and intensity in his manner and technique that is reminiscent of early De Biro. He is also so bright he leaves you with a sense of missing out; multi-layered and talented, you are left with a vague feeling of not quite understanding the finer details of whatever he was explaining and a not so vague feeling on unease. Not scary but definitely unsettling. With a range as extensive as it is nuanced, he is the intellect amongst the current crop of Australian leading men with a resume that includes Zero Dark Thirty, Mudbound, Everest, Terminator and The Planet of the Apes spinoffs.

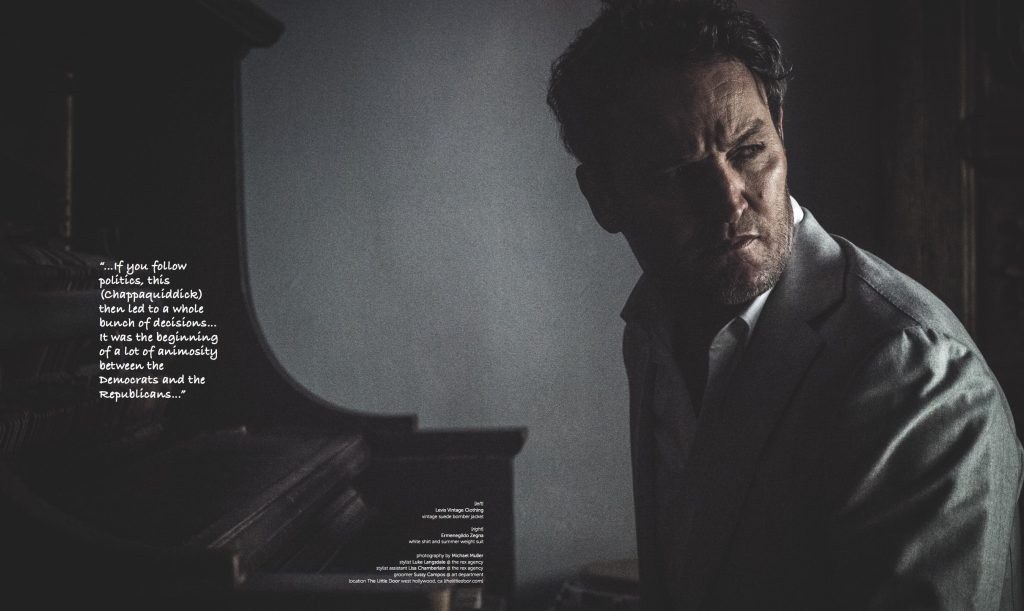

In his latest release, Chappaquiddick, he gives a nuanced and underplayed portrayal of the late Senator Edward Kennedy and the most important—but not only—event that kept the last of the Kennedy brothers out of the White House: a 1969 car accident up in Martha’s Vineyard that resulted in the death of a young woman.

Kennedy left the scene of the crash and didn’t report it to the police for another nine hours, a delay which allegedly cost the young woman, Mary Jo Kopechne, her life. Although Kennedy was universally reviled and ridiculed at the time, Clarke and director John Curran present the retelling of the story in a nonjudgemental almost sympathetic pace that allows us to observe the complexities of the Kennedy clan.

‘The film tries to speak with a larger voice in that you can’t bury everything under the carpet and just point at the opposition and say ‘we’re right, you’re wrong.’ There’s a lot of skeletons in a lot of closets.’

‘There is a great book—one of the best books I read—called The Patriarch which was on Joe Kennedy. That is one of the best biographies I’ve read. One of the titans of the world and American history is Joe Kennedy. One of the things that really struck me, though, really struck me, was on that day, Joe had lost his three sons and this was the day they were taking off for the moon, that Jack OFF() had set in motion ten years previously. And on that day, Ted drives off a bridge and kills a woman, the day that his father is sitting up there watching TV after having had a stroke. That really struck me, that the weight of what he’d done affected everyone. He was father now to Jack’s two kids, Bobby’s eleven kids, and his own one kid. He was father to 14 kids. Ira time of most serious need, he didn’t have a father like his brothers had. His own father was incapacitated. It was what was missing for Ted, rather than what came before him. We put that picture in the end there where he’s reading the speech before he goes on camera with Jack right behind him. That’s always there. In the police station, he’s talking that Jack was this and he was that. He says he’s the bad one.

With a brother and two sisters of his own. Clarke understands the dynamics and tensions in a family. ‘I mean, we tried to bring a lot of that out with his relationship to Joe. He always expected someone else to pick up the pieces. And I think one of his reasons for the nine hours of lapse, he was always used to somebody stepping in and sorting it out. And the hours tick away and he goes to bed and he wakes up the next morning and he expects it to not even have happened in his own snobbish immature way.’

Asked if the timing of making this movie and its exposure of the self-serving nature of a rich spoiled white man is connected to the present occupant of the White House, Clarke responded, ‘One of the best reviews we got out of Toronto (Film Festival( was Owen Gleiberman of Variety and he said ‘this is a reckoning of what we have at the moment.’ The current president…it’s a mess. Everybody knows that. But there’s no sense of the Democrats looking at themselves at all We have one extreme to the other.’

‘This film definitely says something about the situation we’re in today. There’s no partisanship at all. Everybody is out for their own interests and there’s no sense of governing responsibly. In the Democratic Party, you can trace this lineage to Ted Kennedy, to Watergate, to Bill Clinton, to the way everybody is behaving. They go ‘you know what. I don’t have to do this because you didn’t behave well when you were President.’ It gives them license. And you can see this in the way John (Curran( decided to end the film. There are real interviews in the end, and that comes down to our own personal responsibility of not just the dude who’s running or the woman who’s running but that comes down to us as voters, as educated people, knowing our history and knowing what has come before and making informed decisions.’

Clarke opened up about the often overlooked complexities and insecurities of an actor and acting; performing and emoting and being judged on a portrayal of human situations often in a very matter-of-fact situation.

‘You can become very sensitive, to even say a lighting grip looking at his phone when you’re doing it a scene. You think ‘oh my god nobody cares.’ You’re taught to become better and sharper at finding your way to decipher the script and interpret the character, which is what your director needs, but the nerves and the care of what you do never leave. I remember working with Gary Oldman the first time on Apes and I’ve been a massive fan of his for a long time, and I could see even with what he’s done that he was still nervous about doing a scene. It never leaves. Of course you want to be good, but you want to bring everything. Sometimes you can go too big and sometimes you can go too small. You just want to have that space where you can make mistakes.

He is also candid about about his approach to any given scene. ‘I’d rather go over, as a person. On some I’m able to look at scenes and go ‘that’s too much’ or know that less is more. But I think it’s always important I usually try in one of the earlier scenes, second or third take in, to go a bit bigger, to push it out there and just give the director a look at it. You have to feel out the space of either end of the spectrum. I hate the feeling of ‘you know what, I didn’t give enough in that scene, I didn’t go strong enough towards the objective.’ It’s not just size performance but just really playing it hard. That is what directors are for. In this current world—not so much in this film, but in bigger budget films—directors are there to provide that space between the time clock and the producers to say, ‘Ok we can take the time to get this right’ rather than just shoot this and move on.

‘It becomes very clear early on roughly how many takes you’re going to get and what kind of pace you’ve got to move at You know on a big day we’ve got this location to shoot at for 10 hours so we’ve got to move. There are pressures and requirements and you eventually become on board. I also know that as the main actor like on this film, that if I take up all the takes, the other actors get nothing. So you want to make sure. It’s your job and the other actors’ job and the director’s job, it is what it is. And I also find that the pressure make people be on the ball a bit more. It sharpens the mind; you’ve really got to deliver.’

‘A great script is the first contact you have with a movie, but the subject matter also affects which roles you pick. For me it’s subliminal. Before Chappaquiddick, I shot Mudbound where I was playing a less intelligent man. It’s such a different man. So I was really ready to go play someone like Ted. And after Chappaquiddick, I did a World War II film that hasn’t come out yet called The Aftermath about a man who was in charge of putting back Hamburg in the immediate aftermath of World War II. It was just this man who was fighting to actually help the Germans reconstruct after the war rather than just having payback after payback after payback. Post-World War Ills one of the great coming togethers of neighbors who slaughtered each other.’

Something of a Francophile—he is married to a French lady and spends a lot of time in Paris, Clarke is currently working on a pet project in the French capital. ‘I am writing one (a script) with a friend in France that we’ve been working on for some time. I’m interested in geopolitics and history and here we are and why we are, and I’m trying to write something that has to do with that I think it’s interesting times now. There’s so much more information available but so much more disinformation available. If you want to be educated and understand where you are, you have to understand where you’ve come from and look at what’s happening now.’