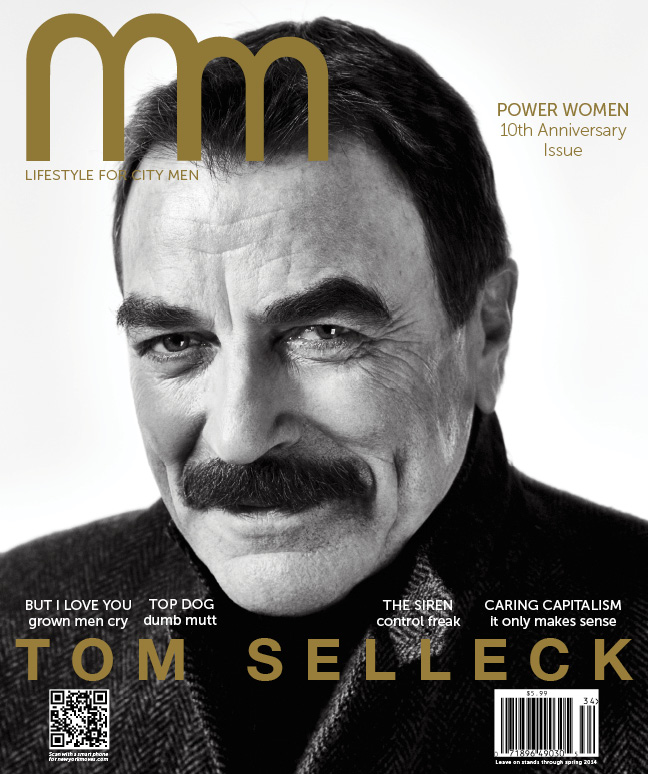

By Chesley Turner

Photography by Darren Keith

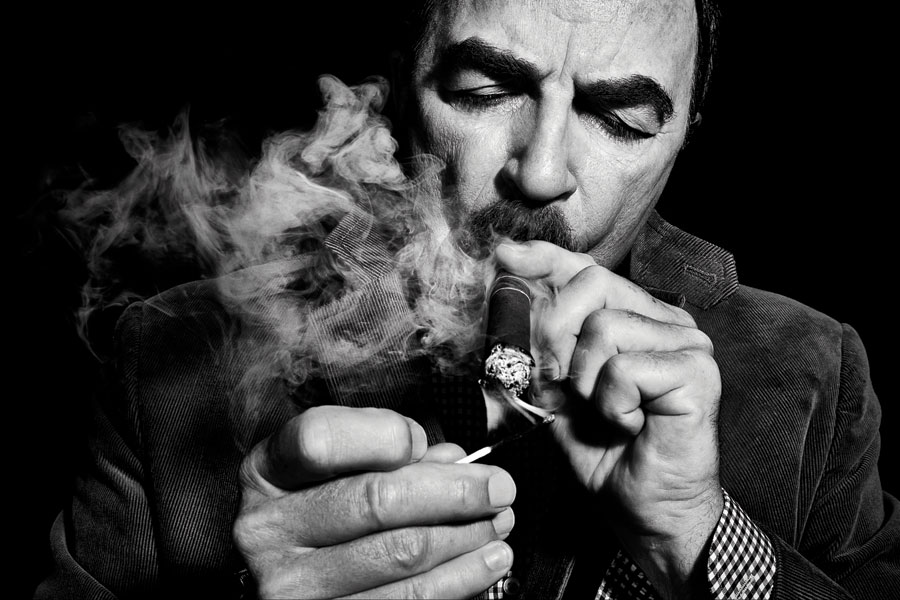

He’s long been recognized as somewhat of a poster-boy for the cult of masculinity. With a mustachioed charm that has wooed more than a few ladies, he is the McDreamy for generations that have come before. And you’d think with that much sway, he might have grown accustomed to throwing his weight around. But Tom Selleck’s first order of business has always been simply to entertain. If he manages to open your eyes a little bit in the process, well that’s okay too.

“What we do in this business is not the truth. We’re pretending. It’s probably a lie that hopefully enables you to see some truth. But what we have to do is get people to suspend disbelief. And characters can do that.” Tom lays out why he holds out for character roles, like Magnum P.I. and Frank Reagan in USA’s Blue Bloods. “The why it is important to me. When you study your craft, you have to know that WHY is a big question.”

But even as he defines his actor’s impetus and the drive behind his creative industry, Tom Selleck is explaining all aspects of his life—not just the ones on screen. Don’t get us wrong; Tom is no crusader. But he’s become rather adept at raising the question: why?

In the early 90’s, Tom says, “I had a rather old-fashioned attitude that when the tabloids would say stuff, that it oughta be true. But I’m also sort of a 1st-Amendment absolutist.” While seeking the right tack to address ethics in journalism, he came across Michael Josephson and the Josephson Institute of Ethics at the University of Southern California. “[Michael] realized that if you start talking about values, there’s a lot of suspicion in today’s culture.” People put any mention of values into the right, or the left, or the religious, or the secular. In order to change that, Josephson had Tom Selleck and Barbara Jordan join forces as national spokespeople. The result was the Character Counts Coalition, which promoted the discussion of character in schools. “I’m very proud of it. It’s based on six pillars: Trustworthiness, Respect, Responsibility, Fairness, Caring, Citizenship. And frankly, that stuff was being avoided because it looked like somebody’s political agenda. But if that’s in a kid’s vocabulary, I don’t think we’ve harmed their soul or their sense of freedom.”

“I think as time goes on, there’s a cultural perversity in the country where people are suspicious. But we have more in common than we do differences and we need to—obviously, even in current events—we need to remind ourselves of that. People would say, ‘What’s your agenda here?’ I don’t have agenda.”

Even as the world gets smaller our egos get bigger, preventing openness to the insights and opinions and perspectives of those who are different than us. “I remember one of the great educations for me was when I went into the National Guard. I had no idea the diversity of the cross-section of the populous of this country. And now technology has made it really easy to just hang out with people you agree with. The next step is to say, ‘Well, I care; therefore people that disagree with me don’t care.’ And you end up with a kind of moral vanity, an attitude of moral preening, whatever your point of view is.”

We can all agree that our current stop-and-start, polarized government is frustrating and in need of a serious lesson in compromise. And Tom, almost dismissively, defines the point of no return: “It’s okay to say, ‘If you disagree with me, I have a problem with that.’ It’s probably okay to say, ‘If you disagree with me, you’re stupid.’ But if you say, ‘If you disagree with me, you’re evil’… that’s reserved for the fringes. We’re supposed to disagree.”

Tom is adamant that he is not a political proselytizer. The nation will survive, he says, not knowing who he endorsed for president. “If you get put in a box, then you can’t reach people.” Tom repeats, again and again, “I’m not a do-gooder. I mean, believe me.” Then, digging into his memory banks of the many times he heard Michael Josephson speak, he quotes the man who catalyzed Character Counts. “’We judge ourselves by our good intentions, but we’re judged by our last worst act. Few of us are as good as we think we are, and none of us are as good as we can be.”

Seamlessly, then, he ties these observations of himself as a well-intentioned but flawed human being to his Blue Bloods character, Frank Reagan. “Frank’s a good man. But it’s not very interesting to watch good people. Hopefully [fans are] saying, ‘I like you, Frank. But I don’t think you should do that.’” Frank Reagan, however, is both a father and a hero. Creators Robin Green and Mitch Burgess, when creating the show, told Tom, “Look. We’ve done the Sopranos and we’ve done anti-heroes. We want to do a show about heroes.”

“That’s a bit dicey because it’s easy to be brave if the script says you’re brave,” Tom, ever the pragmatist, observes. “It’s not like real heroes. So you have to be flawed heroes. Frank is far from perfect. But he’s a patriarch.”

Tom is what one could call a quintessential father figure, and family is precious to him. “I had a really good mom and dad. I could probably go into analysis for 10 years,” he jokes, “and never blame my parents for anything.” He shares a great story about just how strong the family bonds are in the Selleck family. “When my dad passed away, I did two things at the service. First I had to do Rudyard Kipling’s If ‘cause it was his favorite poem. And try to get through that poem when your dad’s just passed. And then I said to the church, ‘He’s the finest man I’ll ever know, and I want to be just like him.’ I don’t think that’s corny. I just think it’s important.”

It isn’t surprising to hear how valued that paternal influence is for a man whose character—on screen and off—is built on driven masculinity with a pronounced honesty, and the occasional softness. Magnum was a heartthrob because Tom Selleck made him that way. But what is surprising is the controversy that surrounded Magnum’s backstory.

It’s a controversy that has to do with Vietnam. And while it’s easy to see the past through rose-colored glasses, the truth is that believing the American soldier was always well-loved is anachronism at its most confused. Magnum was a Vietnam vet, and people didn’t like that. “There was a big fight with networks and everybody else. They didn’t want to have anything to do with Vietnam. This was the first show to recognize Vietnam veterans in a positive light.” Tom talks about how the Hawaiian shirt and Detroit Tiger’s cap and the ring he wore all ended up in the Smithsonian, “probably next to Archie Bunker’s chair and Mary Tyler Moore’s beret.” But in curating those objects out of Magnum’s costume closet, the Smithsonian was recognizing something beyond the show’s obligation to entertain; they were supporting the effort to redefine the American veteran.

“It’s hard, in this current atmosphere, to realize what happened in the Vietnam era to our troops. Obviously one of the biggest lessons that came out in retrospect of the Vietnam era is: We can’t do that to our troops.

“It was a tough time to be in the military, which I was. I think we see now that we grew as a country to realize that you can disagree with the mission, but don’t trivialize or defame the people who went there in good faith.” Even before the Character Counts Coalition, Tom Selleck was subtly effecting a change in popular perception of something that should unite people, not divide them. “I think we treat our returning troops who served in conflict much differently than we did. It’s like night and day. People who returned in uniform were really abused. I never got shot at; I was in the National Guard. But when I got home from active duty, with a certain amount of pride, it was not a pleasant experience, when you’re being called a killer.” The unpopularity of the Vietnam War permeated society, but the outspokenness of its opponents was misdirected. “You can talk forever about the why’s of all that stuff, but there was a serious effort on the part of the anti-war effort to demonize, consciously or unconsciously, the troops. I don’t see that now. We seem to appreciate people when they come home, regardless of what we feel about the conflict. That’s a change. That’s a good change.”

And what powerful women surround this man who promotes large ideals, but in a humble, self-effacing way? They aren’t women who have climbed the corporate ladder or ascended the political hierarchy. They are simply a wife and a daughter.

“I was doing a movie in London and I went to see an old friend of mine perform in Cats. I saw Jillie on stage and met her, and then I went and saw Cats another eight times. Literally.” Clearly, Tom isn’t immune to the charms of a good woman.

Meanwhile their daughter Hannah has the benefit of having a father who will go the extra mile to give her a normal life. “We lied to the press—it’s one of the few times we actually lied to them—about Jillie’s due date.” And on the big day, with a phony limo and a back-entrance exit, “I got her to the ranch. Her first view of life was a 63-acre ranch, and that’s where she grew up.” Now she’s an “Olympic-quality Grand Prix rider, jumping 5- or 6-foot fences, which can get a dad’s heart really thumping.” He talks about her dedication to a sport in which she got no free rides, feeding and grooming and caring for her horses herself every step of the way. “Believe it or not, she’s in a sport where we have to say to her, ‘We can’t afford it!’ That’s a good thing to say to your kids, by the way.”

Beneath that glossy mustache, those twinkling eyes, and the smooth voice of the smooth-talker, there is a man who faces his favorite challenge every day: to be a patriarch.

…And to play one on TV.