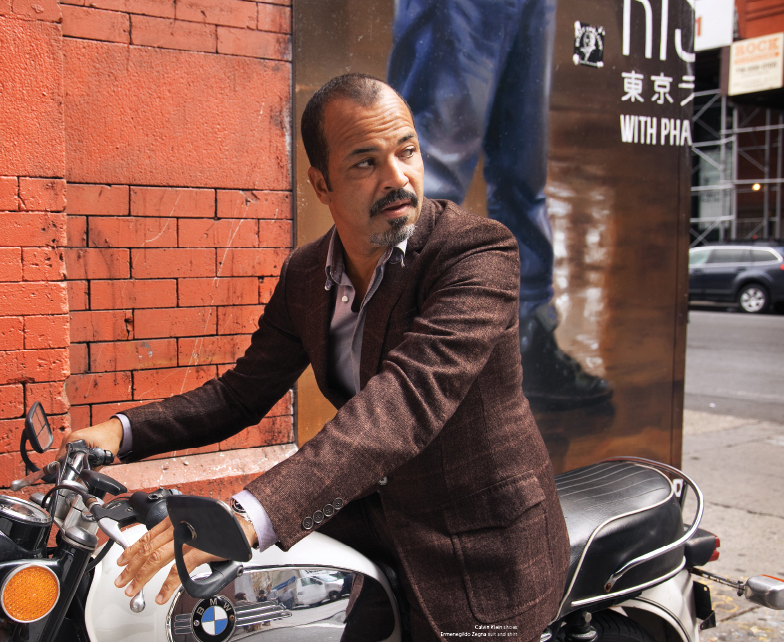

When I first found out that I was interviewing Jeffrey Wright for the Power Issue, clichéd titles sprang to mind (the Wright Stuff etc.) but trying to define a man by punning on his last name is a lame shot, especially once you look at the body of his work in some of Hollywood’s biggest films.

Wright first burst onto the scene playing Julian Schnabel’s Jean-Michel Basquiat (Basquiat), in which he received critical claim. He kept it smooth with Daniel Craig in the Bond series, brokered with George Clooney in Syriana, impersonated Colin Powell in Oliver Stone’s W, was Bill Murray’s go-to friend in Broken Flowers, and most recently played a Senator in The Ides of March with Hollywood darlings Ryan Gosling and Evan Rachel Wood. Oh, and Clooney too. Wright has no shortage of megawatt talent and it’s his meaty roles and star appeal that have made directors fall for him over and over. Next up is Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close with Sandra Bullock and Tom Hanks, the story of a little boy who goes searching for a secret in the wake of 9/11, seeking out the memory of his father who was lost in the Towers.

“Most of us who worked on the film – the cast, crew, director – are all New Yorkers. In many ways it was a way to express emotions and thoughts about the events of 9/11, but deeply for me it was the script… It spoke on a more basic level of family, particularly the relationship between fathers and sons, and that’s what really drew me in, as I have a son myself.”

But it’s Wright’s political and social conscience that should be deemed “extremely loud.” Born in Washington D.C., Wright studied political science at Amherst and received an honorary degree in 2004. “My initial interest in politics emerged at birth. I was born in the 60’s, when that type of interest and concern, [social awareness], was in the air. And as I grew up, kind of a child of the civil rights movement and Vietnam and all that, it kind of shaped my thinking, my inclinations really.”

One thing that wasn’t available in the political arena back then was social media, a tool that can hurt and help someone in office, namely Obama. He addresses the criticism of being the president of the most powerful single nation in the world: “Folks are hurting, everyone feeling the pinch, and obviously that’s got to be a challenging environment to operate as chief executive officer. And at the same time, we’ve all got to be working towards a better way forward. I do think that the dialogue has become so, so, unproductive and unconstructive, and it is so concerning. It becomes, well, that person is not American, that person is not one of us. Coming out of the event of the election of 2008, that brought more people into the fabric of America than ever before. But now the backlash is, the trend is, to cut people off, to cut people out of the fabric, and say people are un-American and un-Patriotic or they’re whatever political term it is that makes them ‘other than’ us. That’s the real shame.”

What’s not shameful is Wright’s dedication of work through the Taia Peace Foundation, the charitable arm of Taia, LLC, formed in 2007 with a focus on Sierra Leone and with a single aim: to assist rural communities in overcoming the so-called “resource curse.” The foundation, a commercial entity, had a lot of resources, and is trying to create a modern 21st century approach to development in Africa, specifically in Sierra Leone.

“The Taia Peace Foundation is looking into opportunities with natural resources and minerals and agriculture, but again trying to do it in a way that is inclusive, of not only the company needs but also the local communities’ needs as well,” says Wright, who is chairman of the Foundation as well as vice chairman of the company, Taia Inc. “Our goal is a long-term goal, and we intend to really be transformational. The critical thing is that there is huge potential for economic growth in these rural communities driven by the natural resource wealth that is there. If it’s harvested in the right way, the natural resources can be used to drive society and can be transformative in the lives of folks who have faced significant challenges relative to the rest of the world.”

I told Wright that one of our main discussion points whenever Africa is brought up in a Moves editorial meeting, is: why aren’t the local governments invested or working to putting an end to this problem? Shouldn’t it be the governments’ responsibility to care for their own people? “Africa is a big continent and like anywhere, visionary leadership comes in handy. One of the things that is so remarkable about [Sierra Leone] is that now, just ten years after what was a pretty brutal civil war, you have two fair elections. It’s the world’s premiere post-conflict success story, but the story has been obscured by our misconceptions about what happened here,” insists Wright, saying that the movie Blood Diamond adversely affected the Western view of Africa. “There are a lot of good things happening to the country, and most of that has to do with the leadership, so again you can’t generalize Africa.”

Wright became involved with The Taia Peace Foundation when he traveled to West Africa for the first time in 1996. After seeing the film Cry Freetown, a story told from the perspective of a few young boys who were caught up in the 1999 rebel invasion in Sierra Leone, it moved Wright deeply.

“From that point on, I became kind of obsessed with what was happening there. The war was fought for […] control of the diamond mining areas, which was the “sexy” story. But it was fought as well because the youth particularly didn’t have a meaningful relationship with their own destiny. It wasn’t born out of a desire to enrich themselves; it was born out of a sense of outrage and intense frustration.”

To Wright, you can’t rebuild nations on altruism, and you can’t play a significant role in helping rebuild people’s lives after trauma through altruism either. It’s just not going to work. “It’s the limitations of peoples’ generosity that will get in the way. What you can do – what I’m a big believer in – is mutual self-interest, finding common ground, and forging meaningful partnerships with people that work through the benefit of both. That’s one of the problems with the Western perception of Africa. We don’t see the continent as having anything to offer us. But if you look at economic growth in the last ten years in Sierra Leone, it’s greater than the United States’ economic growth. China has been about 10.5 percent in that same time, which has been largely driven, or largely fueled I should say, by increasing access to African natural resources. But we as Americans want to view Africa as a liability, as a financial liability, and certainly not an economic partner, which is a mistake because we have an opportunity through partnerships with Africa in the right ways to drive economic growth to this side. Africa has 900 million people, potential consumers of American cars and trucks, mechanizing farms, all matters of opportunities to be explored. But we’re not necessarily viewing it through the right lens.”

What type of impression does the idea of “America” make in Africa? “You see a huge Chinese presence throughout Africa, and I’ve never seen one kid running around the streets of Free Town with a picture of the Premier of China on his shirt. What you do see in parts of the country, so remote, where they only get their news from a battery-powered transit radio, is an image of the president of the United States. It’s incredible.”

There has never been a greater desire for a connection with the United States than there is now in Africa, but it’s not being reciprocated. “We view it really as a historic time, a historic opportunity, an engagement, a 21st century engagement with Africa. We really see Africa as a potential to not only play a part in their own rebirth but also to play a role in our own economic revitalization.”

NOTE: In celebration of Jeffrey Wright’s Best Actor Oscar nomination for American Fiction, the above text is our 2011 profile of Mr. Wright in New York Moves magazine.

Text by Bill Smyth

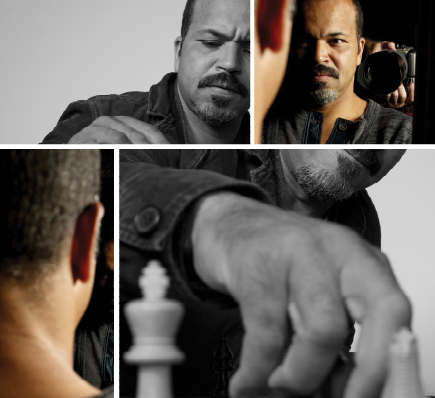

photography by Michael Lavine

stylist Elle Werlin

groomer Rheanne White @ see management