*shampoo – uk slang for champagne

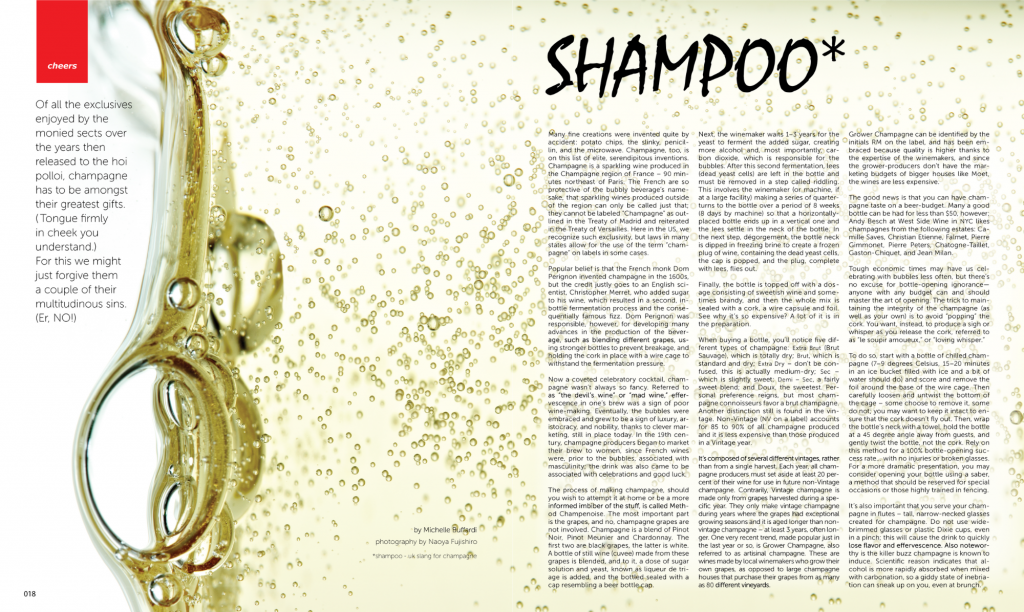

by Michelle Buffardi

photography by Naoya Fujishiro

Of all the exclusives enjoyed by the monied sects over the years then released to the hoi polloi, champagne has to be amongst their greatest gifts. (Tongue firmly in cheek you understand.) For this we might just forgive them a couple of their multitudinous sins. (Er, NO!)

Many fine creations were invented quite by accident: potato chips, the slinky, penicillin, and the microwave. Champagne, too, is on this list of elite, serendipitous inventions. Champagne is a sparkling wine produced in the Champagne region of France – 90 minutes northeast of Paris. The French are so protective of the bubbly beverage’s namesake, that sparkling wines produced outside of the region can only be called just that; they cannot be labeled “Champagne” as outlined in the Treaty of Madrid and reiterated in the Treaty of Versailles. Here in the US, we recognize such exclusivity, but laws in many states allow for the use of the term “champagne” on labels in some cases.

Popular belief is that the French monk Dom Perignon invented champagne in the 1600s, but the credit justly goes to an English scientist, Christopher Merret, who added sugar to his wine, which resulted in a second, in-bottle fermentation process and the consequentially famous fizz. Dom Perignon was responsible, however, for developing many advances in the production of the beverage, such as blending different grapes, using stronger bottles to prevent breakage, and holding the cork in place with a wire cage to withstand the fermentation pressure.

Now a coveted celebratory cocktail, champagne wasn’t always so fancy. Referred to as “the devil’s wine” or “mad wine,” effervescence in one’s brew was a sign of poor wine-making. Eventually, the bubbles were embraced and grew to be a sign of luxury, aristocracy, and nobility, thanks to clever marketing, still in place today. In the 19th century, champagne producers began to market their brew to women, since French wines were, prior to the bubbles, associated with masculinity; the drink was also came to be associated with celebrations and good luck.

The process of making champagne, should you wish to attempt it at home or be a more informed imbiber of the stuff, is called Method Champenoise. The most important part is the grapes, and no, champagne grapes are not involved. Champagne is a blend of Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier and Chardonnay. The first two are black grapes, the latter is white. A bottle of still wine (cuvee) made from these grapes is blended, and to it, a dose of sugar solution and yeast, known as liqueur de triage is added, and the bottled sealed with a cap resembling a beer bottle cap.

Next, the winemaker waits 1–3 years for the yeast to ferment the added sugar, creating more alcohol and, most importantly, carbon dioxide, which is responsible for the bubbles. After this second fermentation, lees (dead yeast cells) are left in the bottle and must be removed in a step called riddling. This involves the winemaker (or machine, if at a large facility) making a series of quarter-turns to the bottle over a period of 8 weeks (8 days by machine) so that a horizontally-placed bottle ends up in a vertical one and the lees settle in the neck of the bottle. In the next step, dégorgement, the bottle neck is dipped in freezing brine to create a frozen plug of wine, containing the dead yeast cells, the cap is popped, and the plug, complete with lees, flies out.

Finally, the bottle is topped off with a dosage consisting of sweetish wine and sometimes brandy, and then the whole mix is sealed with a cork, a wire capsule and foil. See why it’s so expensive? A lot of it is in the preparation.

When buying a bottle, you’ll notice five different types of champagne: Extra Brut (Brut Sauvage), which is totally dry; Brut, which is standard and dry; Extra Dry – don’t be confused, this is actually medium-dry; Sec – which is slightly sweet; Demi – Sec, a fairly sweet blend; and Doux, the sweetest. Personal preference reigns, but most champagne connoisseurs favor a brut champagne. Another distinction still is found in the vintage. Non-Vintage (NV on a label) accounts for 85 to 90% of all champagne produced and it is less expensive than those produced in a Vintage year.

It’s composed of several different vintages, rather than from a single harvest. Each year, all champagne producers must set aside at least 20 percent of their wine for use in future non-Vintage champagne. Contrarily, Vintage champagne is made only from grapes harvested during a specific year. They only make vintage champagne during years where the grapes had exceptional growing seasons and it is aged longer than non-vintage champagne – at least 3 years, often longer. One very recent trend, made popular just in the last year or so, is Grower Champagne, also referred to as artisinal champagne. These are wines made by local winemakers who grow their own grapes, as opposed to large champagne houses that purchase their grapes from as many as 80 different vineyards.

Grower Champagne can be identified by the initials RM on the label, and has been embraced because quality is higher thanks to the expertise of the winemakers, and since the grower-producers don’t have the marketing budgets of bigger houses like Moet, the wines are less expensive.

The good news is that you can have champagne taste on a beer-budget. Many a good bottle can be had for less than $50, however; Andy Besch at West Side Wine in NYC likes champagnes from the following estates: Camille Saves, Christian Etienne, Falmet, Pierre Gimmonet, Pierre Peters, Chatogne-Taillet, Gaston-Chiquet, and Jean Milan.

Tough economic times may have us celebrating with bubbles less often, but there’s no excuse for bottle-opening ignorance— anyone with any budget can and should master the art of opening. The trick to maintaining the integrity of the champagne (as well as your own) is to avoid “popping” the cork. You want, instead, to produce a sigh or whisper as you release the cork, referred to as “le soupir amoueux,” or “loving whisper.”

To do so, start with a bottle of chilled champagne (7–9 degrees Celsius, 15–20 minutes in an ice bucket filled with ice and a bit of water should do) and score and remove the foil around the base of the wire cage. Then carefully loosen and untwist the bottom of the cage – some choose to remove it, some do not; you may want to keep it intact to ensure that the cork doesn’t fly out. Then, wrap the bottle’s neck with a towel, hold the bottle at a 45 degree angle away from guests, and gently twist the bottle, not the cork. Rely on this method for a 100% bottle-opening success rate… with no injuries or broken glasses. For a more dramatic presentation, you may consider opening your bottle using a saber, a method that should be reserved for special occasions or those highly trained in fencing.

It’s also important that you serve your champagne in flutes – tall, narrow-necked glasses created for champagne. Do not use wide-brimmed glasses or plastic Dixie cups, even in a pinch; this will cause the drink to quickly lose flavor and effervescence. Also noteworthy is the killer buzz champagne is known to induce. Scientific reason indicates that alcohol is more rapidly absorbed when mixed with carbonation, so a giddy state of inebriation can sneak up on you, even at brunch.